BlackEnergy, the malware used in a cyberattack that prompted a large-scale blackout in Ukraine in December 2015, has a successor–GreyEnergy. A group is using the malware to target industrial networks outside Ukraine, researchers from Slovakian cybersecurity firm ESET warn.

The researchers said in an October 17–released white paper that analysis of the previously undocumented GreyEnergy group's malware shows it has been used in targeted attacks against critical infrastructure organizations in Central and Eastern Europe.

From Black to Grey

ESET was the firm that first tied the December 2015 attack–the world's first malware-prompted blackout incident, which affected about 1.4 million Ukrainians living in the Ivano-Frankivsk region–to BlackEnergy. The sophisticated malware campaign had compromised several industrial control systems (ICS) using variants since at least 2011, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security's ICS-Cyber Emergency Response Team (CERT) reported in 2014. ESET experts noted in a September 2015 paper that the malware is a trojan that evolved from a simple DDoS trojan since it was first analyzed by Arbor Networks in 2007. It was used in the December 2015 attack to plant a KillDisk component onto the targeted computers that would render them unbootable.

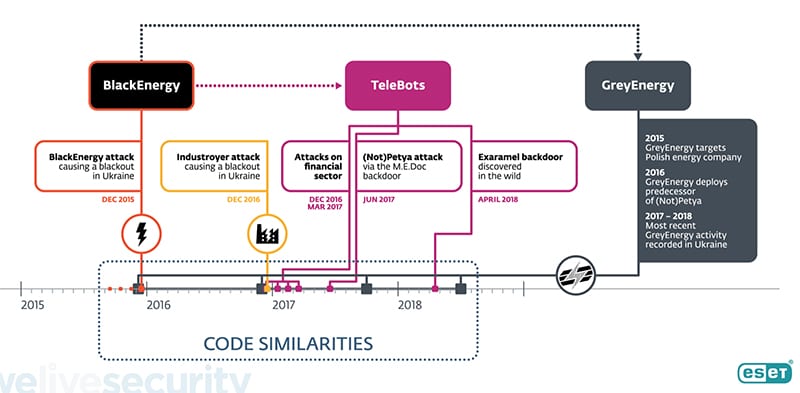

But while the Ukraine attack turned out to be "the last known use of the BlackEnergy malware in the wild," the BlackEnergy group has since evolved into at least two subgroups: TeleBots and GreyEnergy, the researchers warned on Wednesday.

The TeleBots group's primary objective appears focused on cybersabotage attacks in Ukraine, and it has been successful. In December 2016, the group launched a series of attacks using an updated version of the KillDisk malware designed for Windows and LinucOSes against high-value targets in the Ukrainian financial sector. ESET also points to TeleBots for the notorious NotPetya attack in June 2017, which was carried out using a sophisticated backdoor that was embedded into financial software M.E.Doc, which is popular in Ukraine. In October 2017, the group deployed a new variant of NotPetya, BadRabbit, to execute new widespread cyberattacks on several transportation organizations in Ukraine, as well as computer systems in the Kiev Metro, Odessa airport, and also a number of organizations in Russia.

Modular and Dangerous

GreyEnergy, whose design and architecture is "very similar" to BlackEnergy malware, has meanwhile, also been active. "We should say the GreyEnergy group has different goals than the TeleBots group: this group is mostly interested in industrial networks belonging to various critical infrastructure organizations," primarily in the energy sector, followed by transportation, ESET said. "And unlike TeleBots, the GreyEnergy group is not limited to Ukrainian targets."

The firm said it first spotted GreyEnergy malware targeting an energy company in Poland. "At least one organization that had previously been targeted by BlackEnergy [in Ukraine] has more recently been under attack by GreyEnergy The most recently observed use of the GreyEnergy malware was in mid-2018," mostly in Ukraine.

The researchers noted GreyEnergy is modular like Industroyer, the malware linked to the December 2016 cyber attack on Kiev's power grid, which resulted a second power outage that affected 200 MW of capacity. Modularity is of specific concern because threat actors can design and combine modules to disrupt targeted victim systems, for example, backdoor, file extraction, taking screenshots, keylogging, password, and credential stealing.

They also said they have not seen GreyEnergy incorporate any module that is capable of affecting ICS systems. "However, the operators of this malware have, on at least one occasion, deployed a disk-wiping component to disrupt operating processes in the affected organization and to cover their tracks," they said.

Additionally, research showed that GreyEnergy operators have been "strategically targeting ICS control workstations running SCADA software and servers, which tend to be mission-critical systems never meant to go offline except for periodic maintenance."

Research also showed that at least one GreyEnergy sample was signed with a valid digital certificate that had likely been stolen from Advantech, a Taiwanese company that makes ICS equipment. "In this respect, the GreyEnergy group has literally followed in Stuxnet's footsteps," the researchers said. Stuxnet's infamy grew after implication in one of the world's first high-profile cyber attacks specifically targeting ICS, during the 2010 attack at Iran's Bushehr nuclear plant.

A Stealthy Threat

In a blog post, ESET Senior Malware Researchers Anton Cherepanov and Robert Lipovsky noted that despite malware activity over the last three years, GreyEnergy–which they described as an "advanced persistent threat" (APT) group–hasn't been documented before, likely because attacks haven't been as destructive as TeleBot ransomware campaigns, BlackEnergy's 2015 Ukraine grid attack, and Industroyer's December 2016 Ukraine grid attack. They noted ESET only last week established a connection between TeleBots, BlackEnergy, Industroyer, and NotPetya.

"Instead, the threat actors behind GreyEnergy have tried to stay under the radar, focusing on espionage and reconnaissance, quite possibly in preparation of future cyber-sabotage attacks or laying the groundwork for an operation run by some other APT group," they warned.

Of specific concern is that GreyEnergy's malware framework bears many similarities to BlackEnergy. Along with modularity, both employ a "mini", or light, backdoor deployed before administrative rights are obtained and the full version is deployed. Also, all remote command and control (C&C) servers used by GreyEnergy malware were active "Tor relays," or routers on an open network designed to help users defend against traffic analysis. "This has also been the case with BlackEnergy and Industroyer. We hypothesize that this is an operational security technique used by the group so that the operators can connect to these servers in a covert manner," the researchers said.

However, GreyEnergy is even more sophisticated than BlackEnergy. While both use a basic stealth technique to "push only selected modules to selected targets, and only when needed," some GreyEnergy modules are partially encrypted using AES-256 and some remain fileless–running only in memory–with the intention of hindering analysis and detection. "To cover their tracks, typically, GreyEnergy's operators securely wipe the malware components from the victims' hard drives," they added.

Modus Operandi

The researchers said they observed that GreyEnergy employs two distinct infection vectors: "traditional" spearfishing and compromise of public-facing web servers.

Attacks may start with malicious documents, which drop "GreyEnergy mini", a lightweight first-stage backdoor that does not require administrative privileges. After compromising a computer with the mini-version, attackers map the network and collect passwords to obtain administrator privileges. ESET says the group uses "fairly standard tools" for these tasks: Nmap and Mimikatz.

Once initial network mapping has been accomplished, the attackers can deploy their flagship backdoor–the main GreyEnergy malware. "According to our research, the GreyEnergy actors deploy this backdoor mainly on two types of endpoints: servers with high uptime, and workstations used to control ICS environments," they said.

Stealth measures include deploying additional software on internal servers in compromised networks so they can act as a proxy, which could redirect requests from infected nodes inside the network to an external C&C server on the internet. All C&C servers have been Tor relays, the firm said.

Professionals Weigh In on How to Thwart Attacks

According to Boston-based industrial cybersecurity firm CyberX, ESET's research is significant not only because it gives energy operators some awareness of how to protect themselves–but who the perpetrators are. Phil Neray, CyberX vice president of industrial cybersecurity, told POWER on October 18 that the research "credibly ties the sophisticated Ukrainian grid attacks of 2015 and 2016 to NotPetya and hence to the Russian GRU."

Russia is now a prominent focus of the U.S. Department of Defense's (DoD's) newly released cyber strategy, owing to cyber-enabled information operations to influence U.S. democratic processes. However the DoD also points to other actors, such as North Korea and Iran for malicious cyber activities that harm U.S. citizens and threaten U.S. interests.

"One easy takeaway from the research is that organizations should block all outbound access to TOR networks from their internal IT and OT networks, since this threat actor prefers using TOR for communication with its C&C servers," Neray noted.

Moreno Carullo, co-Founder and chief technology officer of San Fransisco–headquartered ICS and SCADA cybersecurity firm Nozomi Networks, told POWER on October 18 that the discovery of yet another undocumented advanced malware was "inevitable." He added: "We are seeing a trend in ICS cybersecurity where this, and other malwares do exist, and they are threatening our world's most critical infrastructures."

Carullo said that an alarming aspect of the trend is that "Each new malware our industry discovers is proving to be more and more advanced, like how this GreyEnergy malware extends its capabilities by receiving the module remotely."

However, he noted the cybercriminals' main attack vectors–compromising public-facing web services and spear-phishing–could be "easily thwarted" with the right ICS solution and necessary training for employees. "With continuous visibility, advanced ICS security and constant education, industrial facilities worldwide can leverage their skills and tools to ensure they aren't at risk to be hit next at a time where industrial controls and critical infrastructure are priority cybersecurity targets," he said.

–Sonal Patel is a POWER associate editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine)

Editor's note: Updated on October 19 to add details from Nozomi Networks