Photo: SSPI

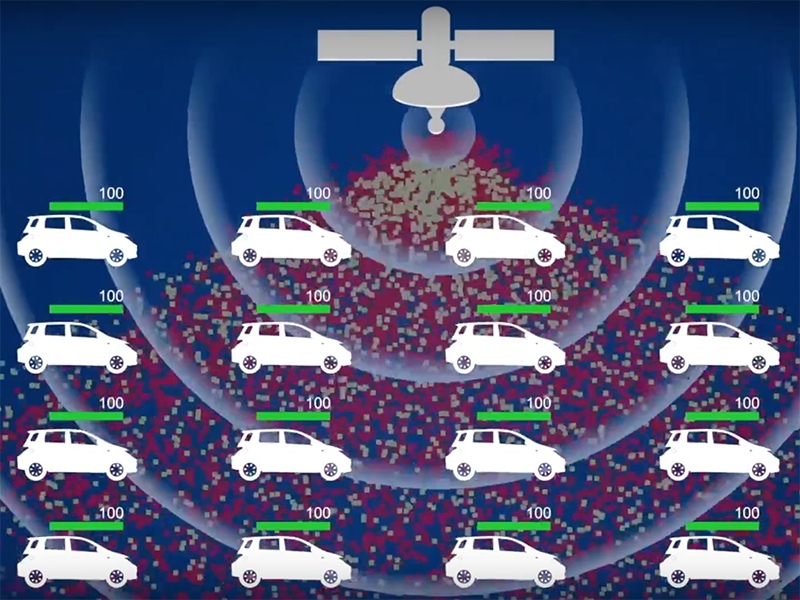

The new generation of connected cars – especially autonomous vehicles – will be a boom market for satellite, says the satellite industry. Not so fast, says the mobile industry. 5G is the future. Signals from space will have nothing to do with it. But, who is right? One? Both? Neither?

Under the Hood

When the subject turns to connected and autonomous cars, what are we really talking about? The average automobile today is already a computer on wheels, running about 100 million lines of software to process about 25 gigabytes of data per hour. There are already millions of connected cars on the road, which generally connect over the same cellular network we use for phones. In fact, in 2016, the growth rate for new car connections in the U.S. outpaced that for phones for the first time.

What do those connections deliver? Typically, internet access and the ability to stream Spotify and Pandora, plus emergency roadside assistance. In other words, the same services you can get from your phone, built into the car. But try streaming Netflix so your kids can watch a TV show, and you quickly learn the limits.

A more important limit, however, is that cellular doesn't go everywhere. As long as we are just talking about entertainment, that's not a serious issue. When we are talking about not dying, it's a different conversation.

As cars become increasingly autonomous, the challenges to connectivity rise. Fully autonomous cars will need incredibly accurate and up-to-date maps to supplement their vision systems. They will need to connect with each other to signal their intentions. And they will need massive software updates as frequently as your mobile phone or tablet, especially in the early days of the technology. Without those updates, the autonomous vehicle could rapidly become a collection of bugs on wheels.

We are talking about a truly massive amount of data. Thank goodness 5G will provide capacity of 1-10 gigabits per second everywhere, right?

The Trials of 5G

Eventually, it may. But the roll-out of 5G will be a decades-long affair during which the mobile network will continue running standards from 2G up to 4G LTE under the 5G umbrella. That umbrella is not even due to take final form until 2020. The first 5G deployments will be in big cities where the vast increase in the number of base stations they require will be offset by the density of paying subscribers squeezed into a small area. As your car takes you to the highways, the suburban streets and the rural roads of your nation, however, you will leave that massive capacity behind for years to come.

That leaves plenty of opportunity for satellites in Geostationary Orbit (GEO), (Medium Earth Orbit) MEO, and Low Earth Orbit (LEO) to fill the gap, particularly where they can exploit the traditional one-to-many technology advantage. Map and software updates are one example. Entertainment is another, as satellite TV to the car joins satellite radio, which is still adding more than a million new subscribers per year in the U.S.

The much-anticipated success of LEO constellations adds even greater opportunity: making available a competitively-priced internet connection everywhere, backing up the terrestrial network so that subscribers can look forward to a seamless, high-quality experience. "Competitively-priced" is the key phrase. Whatever the orbit, service must be excellent, and the price be affordable. Otherwise, the industry risks recreating the debacle of early internet-via-satellite offerings, which charged high prices for over-contended service.

If the industry is successful in seizing the connected and autonomous car opportunity while 5G rolls slowly out, we can even dare to envision a future in which the biggest role for terrestrial wireless is in communication between cars, which may require a massive share of all those gigabits.

Going to Ground

Pricing concerns are not reserved for the sky. At a recent satellite regulatory conference I attended in Washington, D.C., one speaker made a striking point. With all the attention paid to massive LEO constellations, it is rapidly becoming clear that the single most important success factor for LEO broadband is on the ground.

The U.S. market bought 17 million cars in 2017. To equip that many cars, the antennas have to be pretty cheap, as well as reliable, versatile, and powerful. Forget $50 thousand or $30 thousand or even $15 thousand per antenna – the kind of numbers that work for commercial aircraft or super-yachts. One company that has built this reality into its design is Kymeta, which is in tests with Toyota, and in serious discussions with other manufacturers.

Serving a mass market like automotive will take mass-market pricing, and every successful innovator of flat-panel, electronically-steered antennas is going to march to the beat of the consumer drum. After the billions invested in new LEO ventures, it is ironic that the future of satellite and the connected car is literally in their hands.

Robert Bell is executive director of the Space & Satellite Professionals International. SSPI produces the Better Satellite World campaign, which dramatizes the immense contributions of space and satellite to life on Earth. More at www.bettersatelliteworld.com.

Robert Bell is executive director of the Space & Satellite Professionals International. SSPI produces the Better Satellite World campaign, which dramatizes the immense contributions of space and satellite to life on Earth. More at www.bettersatelliteworld.com.