The way IBM sees it, artificial intelligence (AI) can help expedite the OODA loop – the decision-making cycle of observe, orient, decide and act theorized by U.S. Air Force Col. John Boyd.

Speaking at Modern Day Marine at Marine Corps Base Quantico in Virginia Wednesday, Juliane Gallina, the company's VP of U.S. federal key accounts, said that AI's role is to bolster the orient and decide parts of that process. Since Boyd's day, she said, the military has focused on adding more sensors to gather more information, but "ultimately, we bogged ourselves down because we can't orient well. We need to make sense of it all."

According to Gallina, the goal is an all-encompassing AI that can draw from vast knowledge reserves and extensive learning to opine on any situation – she provided Iron Man's JARVIS AI assistant as an example. But that is unrealistic. She said what IBM and many other companies choose to do is take narrow fields and train machines to be experts there: like a Nest thermostat.

"Nest is useful but specific," Gallina said. "It has a narrow cognitive function, but it does it well and efficiently. It probably does it better than you could because you don't want to be standing at the thermostat all the time adjusting the temperature. It can't call your mom. It can't recommend tactical advantages to a Marine. But it does what it does well."

There are similar examples in other fields. Gallina said the most exciting potential is chaining those specific AIs together to create something closer to the JARVIS fantasy. IBM has exposed its Watson cognitive computing as an open application programming interface (API) so people can use it as make narrow programs and use them as "the building blocks of AI today."

Among the applications for IBM's AI building blocks include Korean Airlines' Airbus airplanes with predictive maintenance support, letting the company know when a part would fail as well as what needs to be done to fix it.

The same service has been used as a trial with the U.S. Army for its IAV Stryker armored vehicles. Gallina said if the program had been live throughout the service, predicting things such as when suspension would fail could have saved millions of dollars already.

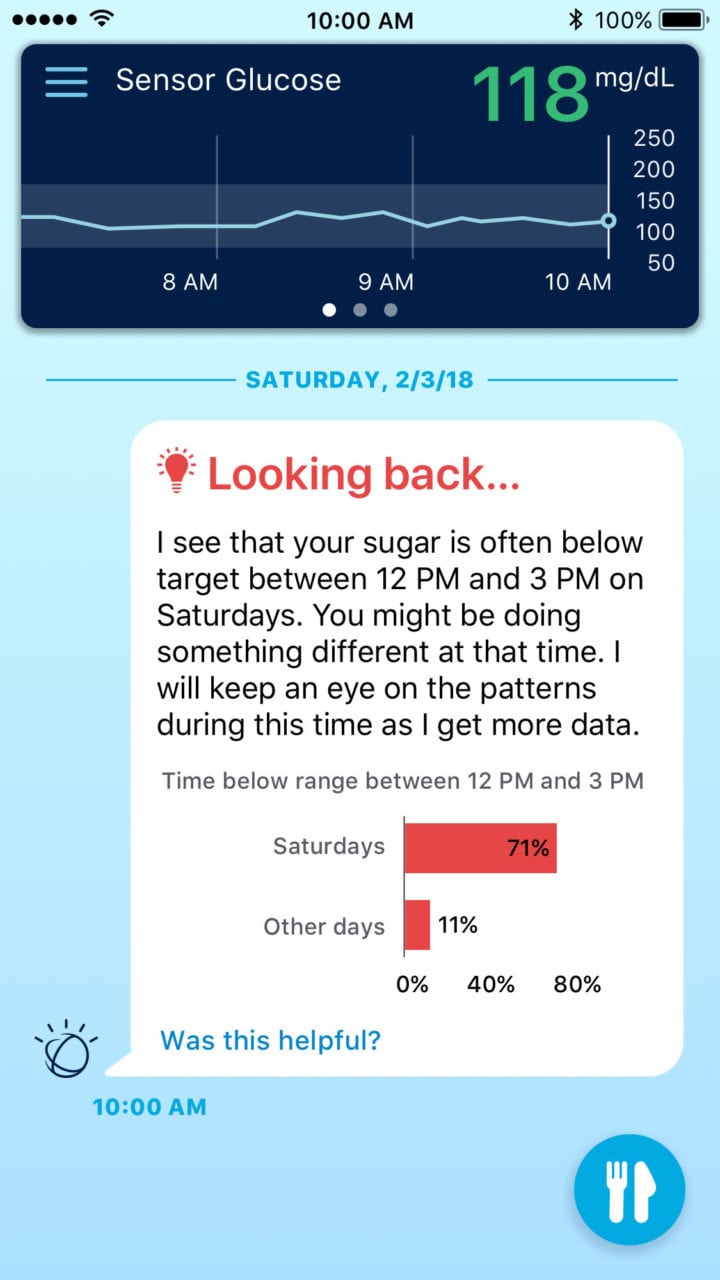

IBM's AI API is the foundation for specific applications running the gamut from supply chain oversight to this glycemic index monitor. (IBM)

Beyond simply predicting what parts would fail and when, Gallina said, the AI would be able to memorize and search technical manuals for equipment, so when something is needed or would soon need replacing, it could pull up the relevant instructions and send them to the maintenance technician. That could even go a step farther and involve finding online videos, instructional comics or whatever would be most helpful for the technician – part of the idea is that the AI could learn the habits of people and how to support them most effectively and, in this case, what information would be most useful to send to their tablet.

Whether it's repairing a fighter jet, providing a cancer treatment plan or monitoring a network for anomalous activity, it is crucial that an AI is transparent about how it arrives at its decisions and recommendations. It is useful that an AI can consider near-infinite historical examples and more research than any human could, then quickly integrate and weigh them, but that can't be a closed process with no accountability or oversight. "Explainability" is a core fundamental of AI design at IBM for that very reason, according to Gallina, so a layperson can check and see why a system arrived at a decision – perhaps via a clickthrough of what evidence it primarily used and how it weighed that evidence.

With the internet of things and constant cloud connectivity, companies and the military are pulling in more data than they can process. IBM is looking at it through the lens of the OODA loop and considers AI the ally people need to get through it, spinning that loop faster around to action.