Personal wearable technology, which covers the gamut from activity trackers such as Fitbit to e-textiles that monitor vital signs, have the potential to revolutionize healthcare. Like most innovations, however, the technology comes with risks.

For OR leaders, those risks include possible security breaches, distractions, and violation of patient privacy and confidentiality. "As with all new technology, there is a need to proceed with caution," says Mary Jane Edwards, RN, CNOR, FACHE, national director for Deloitte Consulting LLP. "Personal wearable technology introduces the risks of anarchy, uncertainty, and privacy concerns into the OR."

Here is what OR leaders need to know about personal wearable technology (PWT).

Edwards defines these components as "small, electronic devices worn close to the body, on the body, or, in some cases, in the body."

The focus in this article is on single-function devices used for health.

A booming industry

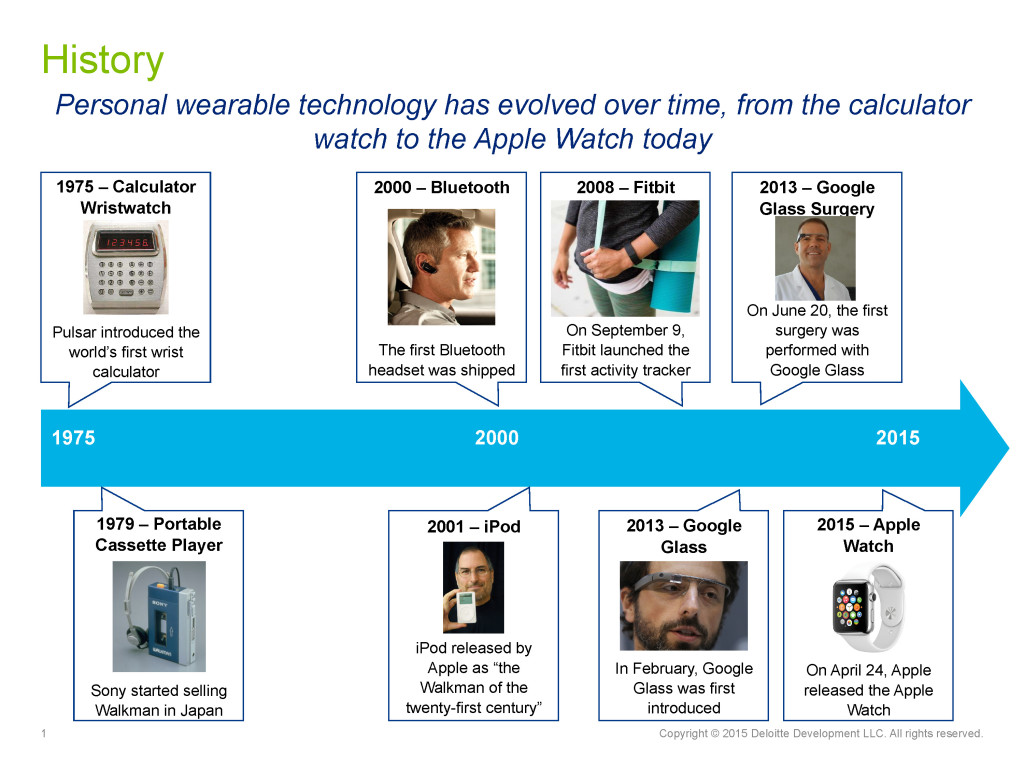

PWT's roots date back to the Vietnam War, when helicopter pilots used mobile communication and visualization through their headsets. In 1975, Pulsar introduced the first wrist calculator, which was soon followed by the Sony Walkman in 1979. But the explosive growth started in 2000 when the first Bluetooth headset was shipped (sidebar, p 17).

According to Edwards, the market for the Apple Watch and Fitbit increased by 225% from 2014 to 2015. This growth is expected to continue: The PWT market was projected to grow from $22 billion to $90 billion between 2015 and 2020, according to a report from Research and Markets.

"Today there are 4.9 billion devices," Edwards says. "The world population is about 7.9 billion, and [the Gartner company] estimates that by 2020, there will be over 20 billion devices connected to the Internet."

PWT in the OR

"What are we going to do in the OR with all that information from all those devices?" Edwards asks. She answers the question by noting that PWT has been purported to have three main roles in surgery:

• augmentation: real-time delivery of information to surgeons

• assistance: replacement of physical tasks

• assessment: measurement of disease severity or clinical status and outcomes.

Google Glass

A device that falls into the assistance and augmentation realms is Google Glass–glasses with a camera, monitor display, connectivity through Bluetooth and Wi-Fi, and memory storage that synchs with Google cloud service.

On the consumer level, Google Glass had a rapid rise and fall, from its warm reception at Diane von Furstenberg's 2013 show during spring's New York Fashion Week, to being named "the worst product of all time" in September 2014 by Geek Beat, the technology news website.

In January 2015, Google shut down its Glass Explorer program and transferred the Glass to another department, where at some point it's expected to be redesigned and released as a new product.

Edwards says the product failed for a number of reasons, including the release of a prototype instead of a final product, lack of a specific enough purpose for the device, and bad timing. (At the time, Google was under scrutiny for its privacy policy.)

However, Edwards says, "There are plenty of advocates for Google Glass within the surgical world."

Among those advocates is general surgeon Rafael Grossmann, MD. In 2013, Dr Grossman performed the first surgery with Google Glass: a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Although Dr Grossman has identified some design problems, "I think it's fair to say that his opinion is the benefits outweigh the risks," Edwards says.

Dr Grossman and other surgeons have streamed various procedures to multiple viewers, and another surgeon uses Google Glass to view preloaded x-ray images during surgery. Edwards says that although the original version of Google Glass is "dead," more than two dozen other companies are developing smart glasses, so the technology will continue.

History of personal wearable technology

Source: Mary Jane Edwards, RN, CNOR, FACHE.

Source: Mary Jane Edwards, RN, CNOR, FACHE.

Activity trackers

Another PWT product of interest to OR leaders is the activity tracker, already being used in other industries. For example, some long-haul trucking companies use activity trackers to check driver alertness.

"Suppose there was something in the OR where perioperative staff vital signs could be monitored and compared to scientifically accepted criteria for fatigue?" Edwards asks. Activity trackers could alert staff, possibly avoiding errors that occur as a result of fatigue.

Real-time information

Benefits of PWT potentially begin before the patient reaches the hospital, let alone the OR. For example, responders could transmit real-time audio and video to the hospital to provide information staff could use to prepare for the patient. "You would know which staff members to bring in and what is needed to meet the needs of the incoming patient," Edwards says.

During surgery, surgeons already are sharing video of operations for educational purposes and to help the surgical team better anticipate what needs to be done.

"It's the transmission and reception of information in real time," Edwards says. "There's the ability to course correct in the moment and the opportunity for surgeons to confer with each other and provide remote assistance."

For example, a surgeon in Birmingham, Alabama, and a surgeon in Atlanta were able to collaborate on a shoulder replacement surgery. This type of assistance is ideal for resource-challenged areas where expertise is not locally available.

"Think how valuable that would be," Edwards says. "To literally have the patient on the table, be able to dial in another surgeon through live streaming so that surgeons can look at the situation together and make a decision in real time instead of having to close up the patient and send him for another surgery elsewhere." Of course, patients would need to give informed consent for this type of sharing.

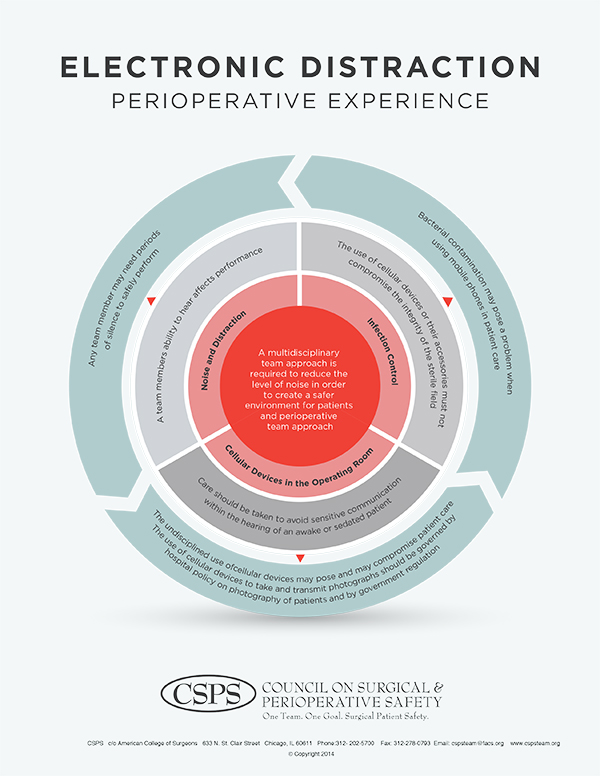

Electronic distraction: Perioperative experience

This infographic from the Council on Surgical & Perioperative Safety can help guide the development of education programs and policies.

Source: Council on Surgical & Perioperative Safety. Reprinted with permission.

Risks of PWT

Perhaps the biggest concerns with PWT are security and privacy. "There are ever-increasing numbers of data breaches across many industries, including healthcare," Edwards says.

According to the 2015 Cybersecurity Survey from HIMSS, two-thirds of healthcare organizations experienced a significant security incident in the past year, with 21% of those reporting loss of patient, financial, or organizational data.

PWT products may not have sufficient security protections. For example, Edwards says that with the original Google Glass, information flowed through Google's unprotected servers before being stored in the cloud, and some experts worry about cloud security.

Edwards notes that these concerns have prompted the development of new products such as EyeSight, from Pristine (Austin, Texas), which provides a video platform for use of smart glasses. According to the company, the platform has data encryption and is HIPAA compliant.

Edwards adds that it's not always clear what to do with the additional information available from PWT.

"Suppose before you go into surgery, all your Fitbit information downloads into your medical record," she says. "Who is supposed to do something with that? Will the nurse be expected to review that and take action based on it?"

Another concern with PWT is distraction of OR staff and surgeons from the task at hand. For example, Edwards cites a study in which 55% of cardiopulmonary technologists who monitor bypass surgery admitted to talking on their phones during surgery; 50% admitted to texting.

Furthermore, most OR leaders can share stories of clinicians checking emails or surfing the Internet using their smart phones during surgery. Some surgeons even use Bluetooth technology to take calls.

Even if security breaches and distractions can be avoided, PWT products still carry another risk–bacterial contamination. "Think about how clean your cell phone is," Edwards says, adding, "Would you be willing to kiss your phone?"

Keeping the OR safe

Edwards suggests that OR leaders provide education about PWT to staff and work with their teams to establish policies and guidelines for use of PWT in the OR to keep patients safe. Things to cover include when PWT devices can be used, restrictions on video and audio recording, and security guidelines.

One resource is the "Electronic Distraction: Perioperative Experience" infographic from the Council on Surgical & Perioperative Safety (sidebar at right).

Other resources include guidelines from associations such as AORN, the American College of Surgeons (ACS), and the American Association of Nurse Anesthetists.

Edwards acknowledges that even with recommendations, it can be hard to manage PWT.

For example, the ACS says, "Surgeons should only engage in urgent or emergent outside communication during surgery," but as Edwards says, "I've been in the OR long enough to know that definitions of urgent and emergent are very situational."

Edwards also recommends working with the information technology (IT) department to fully understand guidelines related to data sharing and how information is backed up, including use of a cloud provider.

She notes that the frontline defense for keeping data secure in any cloud system is encryption, which uses complex algorithms to conceal cloud-protected information.

Although encryption falls under the domain of the IT department, Edwards recommends that perioperative leaders understand the levels of encryption used in their facilities.

When developing policies, OR leaders should consult with their human resources departments and attorneys to avoid violating guidelines from the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). Of particular importance is using PWT to record others.

Stan Hill, an attorney with expertise in labor law, writes, "Employers may prohibit employees from copying or disclosing confidential or proprietary information about the employer's business, using wearable technology or otherwise."

However, the organization must be careful not to word policies in such a way that the NLRB views them as inhibiting employees from discussing workplace conditions such as wages, he notes. "Employers should consider revising their anti-harassment and conduct policies to prohibit the use of wearable technology, including its recording features, in an unlawful manner," Hill says.

Potential for wide benefit

"Personal wearable technology, if properly used, has the potential to greatly improve the efficiency and accuracy of the healthcare delivery by surgeons and the perioperative team. But we have to educate staff and surgeons and put policies in place to ensure it's used appropriately, Edwards says." ✥

References

Bilton N. Why Google Glass broke. New York Times. Published online February 4, 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/05/style/why-google-glass-broke.html.

Eagan J. 3 issues to be addressed before Google Glass takes off in the operating room. Wearables.com. Published online May 30, 2015. http://www.wearables.com/google-glass-medicine-surgery/.

Edwards M J. Wearable technology in the OR. OR Business Management Conference, 2016.

Gartner says 6.4 billion connected "things" will be in use in 2016, up 30 percent from 2015. November 10, 2015. Press release.http://www.gartner.com/newsroom/id/3165317.

Griffin Jr R F. Report of the general counsel concerning employer rules. Memorandum GC 15-04 from the Office of the General Counsel, National Labor Relations Board. March 18, 2015. https://www.nlrb.gov/search/all/Report%20of%20the%20general%20counsel%20concerning%20employer%20rules.

Grossman R. "OK Glass: hand me the scalpel, please…" Google Glass during surgery! http://www.rafaelgrossmann.com/ok-glass-pass-me-the-scalpel-please-googleglass-during-surgery/.

Hill S. Regulating the recording features of personal wearable technology in the workplace. Polsinelli. Published online December 7, 2015. http://www.polsinelliatwork.com/blog/2015/12/7/regulating-the-recording-features-of-personal-wearable-technology-in-the-workplace.

HIMSS. 2015 HIMSS cybersecurity survey executive summary. June 30, 2015. http://www.himss.org/2015-cybersecurity-survey/executive-summary.

Research and Markets. Global wearable electronics & mobile healthcare sensors market to 2015-2019: Apple, Samsung, Xiaomi, and Huawei are now competing for a slice of the $95 billion pie. June 9, 2015. http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/global-wearable-electronics--mobile-healthcare-sensors-market-2015-2019-apple-samsung-xiaomi-and-huawei-are-now-competing-for-a-slice-of-the-95-billion-pie-300111029.html.

Richtel M. As doctors use more devices, potential for distraction grows. New York Times. Published online December 14, 2011. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/15/health/as-doctors-use-more-devices-potential-for-distraction-grows.html?_r=0.

Slade Shantz J A, Veillette C J. The application of wearable technology in surgery: Ensuring the positive impact of the wearable revolution on surgical patients. Front Surg. 2014;19(1):39.

Save